With the Covid-19 pandemic and its many scares, life on Earth can be overwhelming to many of us. That’s why it can be refreshing to look somewhere else and Gemini Observatory recently released something truly exciting to look at – a fascinating picture of Jupiter that is one of the highest resolution images of the planet taken on Earth.

The scientists behind the Gemini North telescope released the stunning image in their blog post on May 7, 2020. They used a technique called “lucky imaging” and collected thousands of snapshots of Jupiter through the years that they finally collected and merged into a single composite. The sharp details of the planet’s surface are the result of the tedious work process that involved sifting through thousands of photos to find the sharpest ones.

More info: Gemini Observatory

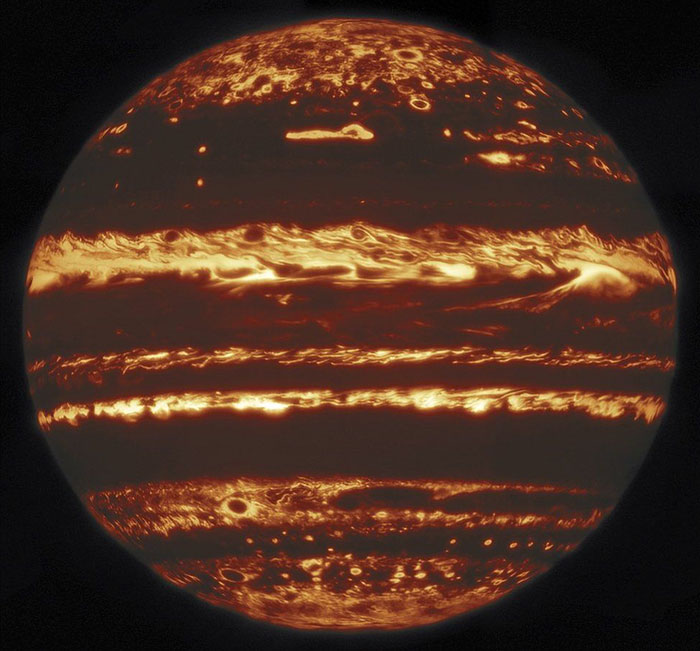

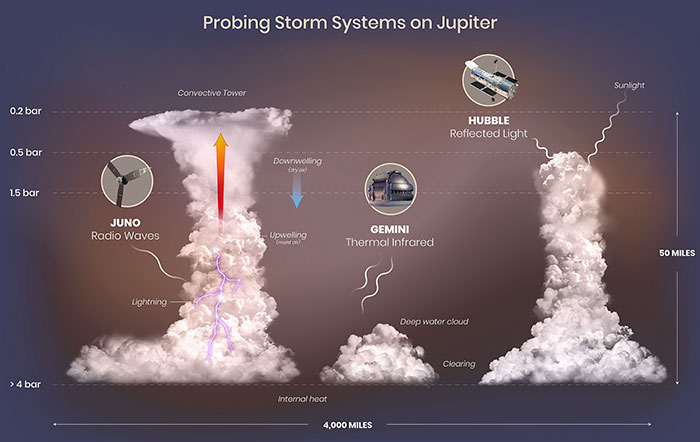

The image shows the entire disk of Jupiter in infrared light

Image credits: Gemini Observatory

Scientists of the observatory provided some additional (and pretty interesting) details on the process:

“Researchers using a technique known as “lucky imaging” with the Gemini North telescope on Hawaii’s Maunakea have collected some of the highest resolution images of Jupiter ever obtained from the ground. These images are part of a multi-year joint observing program with the Hubble Space Telescope in support of NASA’s Juno mission. The Gemini images, when combined with the Hubble and Juno observations, reveal that lightning strikes, and some of the largest storm systems that create them, are formed in and around large convective cells over deep clouds of water ice and liquid. The new observations also confirm that dark spots in the famous Great Red Spot are actually gaps in the cloud cover and not due to cloud color variations.”

So not only did their hard work result in such a stunning photo, it also revealed some interesting information about Jupiter and its clouds.

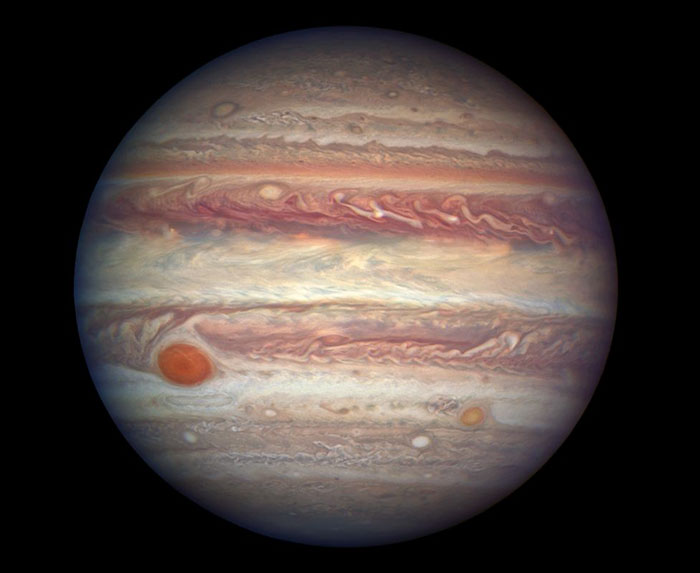

You can compare Gemini’s image of Jupiter with that of NASA Hubble Space Telescope’s

Image credits: NASA

The above photo is what most of us imagine when someone mentions Jupiter and we have this image thanks to the Hubble Space Telescope. Pretty colorful, right? So, you might be asking why the Gemini photo looks like a lava pancake? Well, the Gemini Jupiter photo is in infrared light!

“From a lucky imaging set of 38 exposures taken at each pointing, the research team selected the sharpest 10%, combining them to image one ninth of Jupiter’s disk. Stacks of exposures at the nine pointings were then combined to make one clear, global view of the planet. Even though it only takes a few seconds for Gemini to create each image in a lucky imaging set, completing all 38 exposures in a set can take minutes — long enough for features to rotate noticeably across the disk. In order to compare and combine the images, they are first mapped to their actual latitude and longitude on Jupiter, using the limb, or edge of the disk, as a reference. Once the mosaics are compiled into a full disk, the final images are some of the highest-resolution infrared views of Jupiter ever taken from the ground”

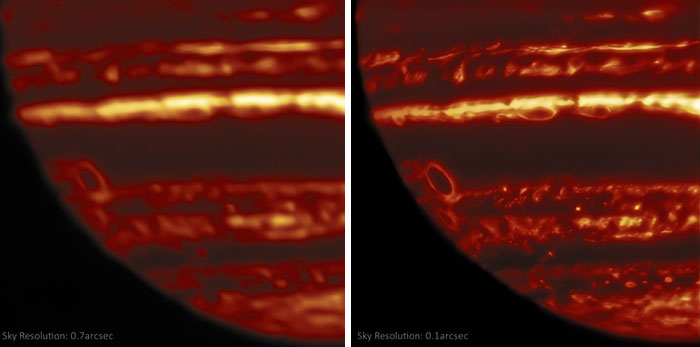

The comparison of sharp and unsharp pictures from lucky imaging process

Image credits: Gemini Observatory

“Because the telescope must observe through the Earth’s atmosphere, any disturbances in the air such as wind or temperature changes will distort and blur the image (left). This greatly limits the resolution the telescope can achieve on a target when only one image is taken. However, during a single night of lucky imaging observations, the telescope takes hundreds of exposures of the target. Some will be blurred, but many exposures will be taken when the view to space is still and clear of disturbances (right). In these lucky images, much smaller, more complex details on Jupiter are revealed. The research team finds the sharpest of these exposures, and compiles them into a mosaic of the whole disk.”

Image credits: Gemini Observatory

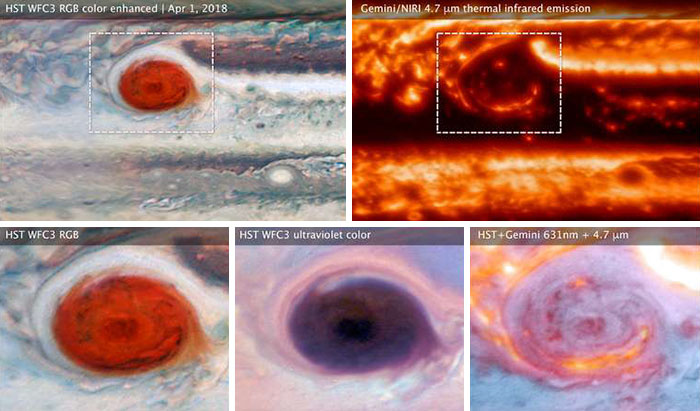

These images of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot were made using data collected by the Hubble Space Telescope and the international Gemini Observatory

Image credits: Gemini Observatory

“By combining observations captured at almost the same time from the two different observatories, astronomers were able to determine that dark features on the Great Red Spot are holes in the clouds rather than masses of dark material. Upper left (wide view) and lower left (detail): The Hubble image of sunlight (visible wavelengths) reflecting off clouds in Jupiter’s atmosphere shows dark features within the Great Red Spot. Upper right: A thermal infrared image of the same area from Gemini shows heat energy emitted as infrared light. Cool overlying clouds appear as dark regions, but clearings in the clouds allow bright infrared emission to escape from warmer layers below. Lower middle: An ultraviolet image from Hubble shows sunlight scattered back from the haze over the Great Red Spot. The Great Red Spot appears red in visible light because the haze absorbs blue wavelengths. The Hubble data show that the haze continues to absorb even at shorter ultraviolet wavelengths. Lower right: A multiwavelength composite of Hubble and Gemini data shows visible light in blue and thermal infrared in red. The combined observations show that areas that are bright in infrared are clearings or places where there is less cloud cover blocking heat from the interior”.

Illustration shows Jupiter’s cloud structure and what data is collected

Image credits: Gemini Observatory

“This illustration of lightning, convective towers (thunderheads), deep water clouds, and clearings in Jupiter’s atmosphere is based on data collected by the Juno spacecraft, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the international Gemini Observatory, a program of NSF’s NOIRLab. Juno detects radio signals generated by lightning discharges. Because radio waves can pass through all of Jupiter’s cloud layers, Juno is able to detect lightning in deep clouds as well as lightning on the day side of the planet. Hubble detects sunlight that has reflected off clouds in Jupiter’s atmosphere. Different wavelengths penetrate to different depths in the clouds, giving researchers the ability to determine the relative heights of cloud tops. Gemini maps the thickness of cool clouds that block thermal infrared light from warmer atmospheric layers below the clouds. Thick clouds appear dark in the infrared maps, while clearings appear bright. The combination of observations can be used to map the cloud structure in three dimensions and infer details of atmospheric circulation. Thick, towering clouds form where moist air rises (upwelling and active convection). Clearings form where drier air sinks (downwelling). The clouds shown rise five times higher than similar convective towers in Earth’s relatively shallow atmosphere. The region illustrated covers a horizontal span one third greater than that of the continental United States”.

Here’s how people reacted to the image

from Bored Panda https://ift.tt/2zpjCZZ